Sir Roger Penrose is certainly one of the great scientists of our time, winner of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work reconciling black holes with Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Born on August 8th, 1931, in Colchester, Essex, he is a renowned British physicist, mathematician, and philosopher. His groundbreaking contributions to the fields of mathematics and theoretical physics have left an indelible mark on our understanding of the universe, black holes, and the nature of reality itself.

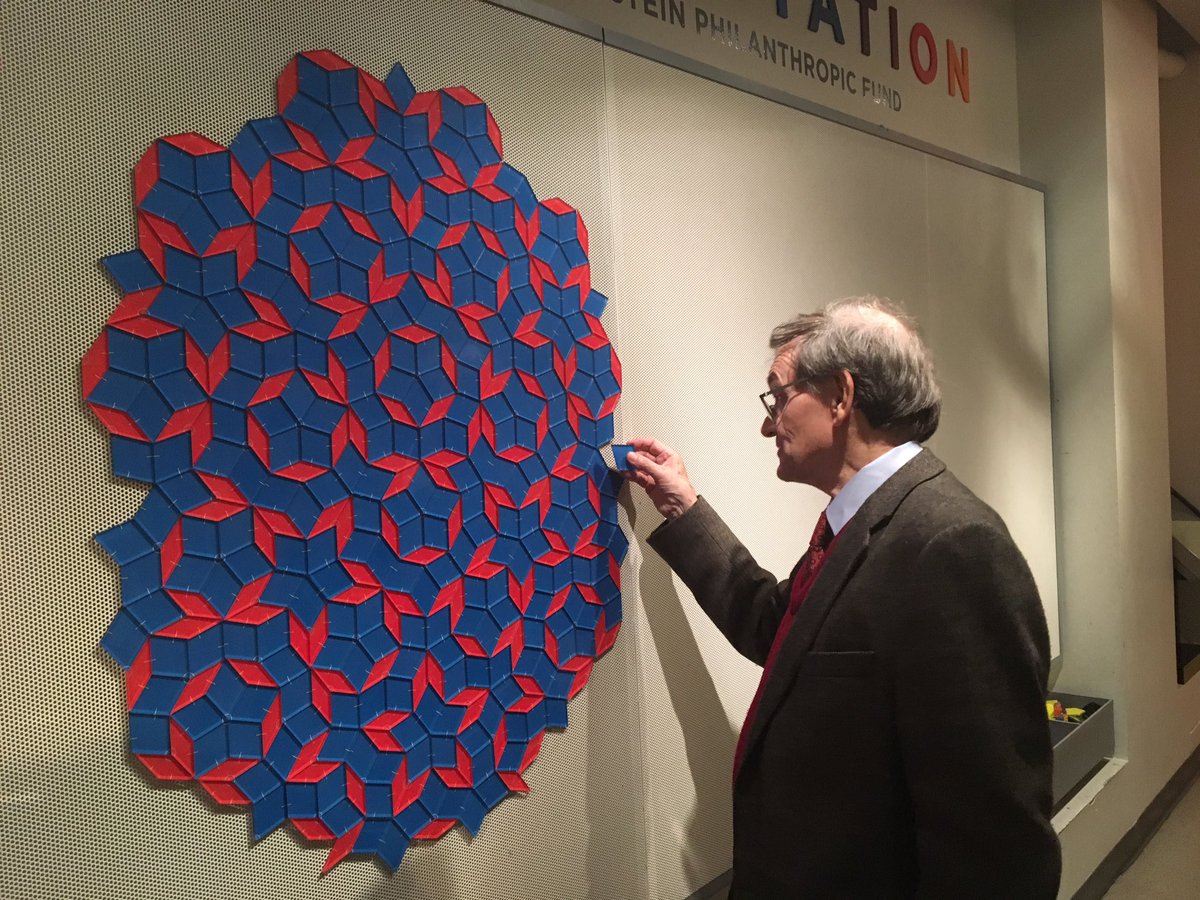

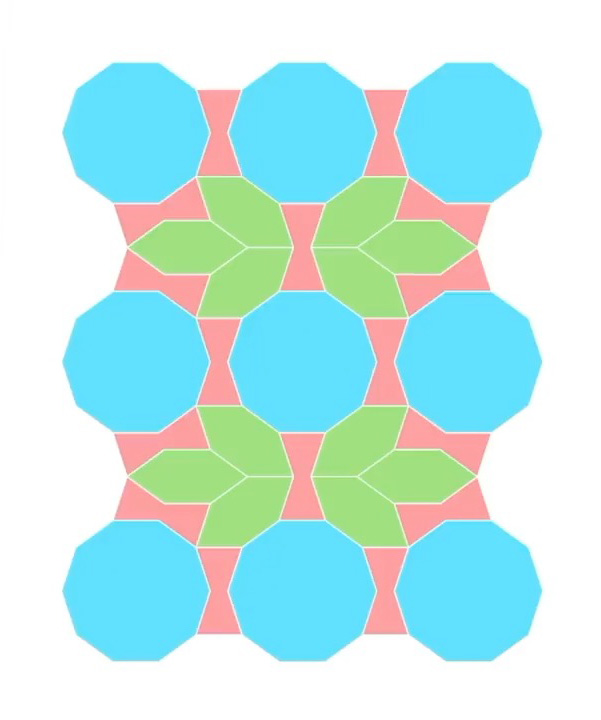

Penrose’s mathematical work has been profoundly influential, particularly in the realm of geometry and the study of space-time. He introduced innovative ideas in the field of tiling, creating the famous “Penrose tiles” – a set of non-periodic shapes that fit together to cover a surface without repeating patterns. This work laid the foundation for a new branch of mathematics known as “quasicrystals.”

The remarkable thing about the pattern that Roger Penrose developed is that by using only two shapes, he constructed a pattern that could be expanded infinitely in any direction without ever repeating. Much like the number Pi has a decimal that isn’t random, but it will go on forever without repeating.

In mathematics, this is a property known as A-periodicity. The notion of an A-periodic tile set using only two tiles was such a sensation it was given the name Penrose tiling.

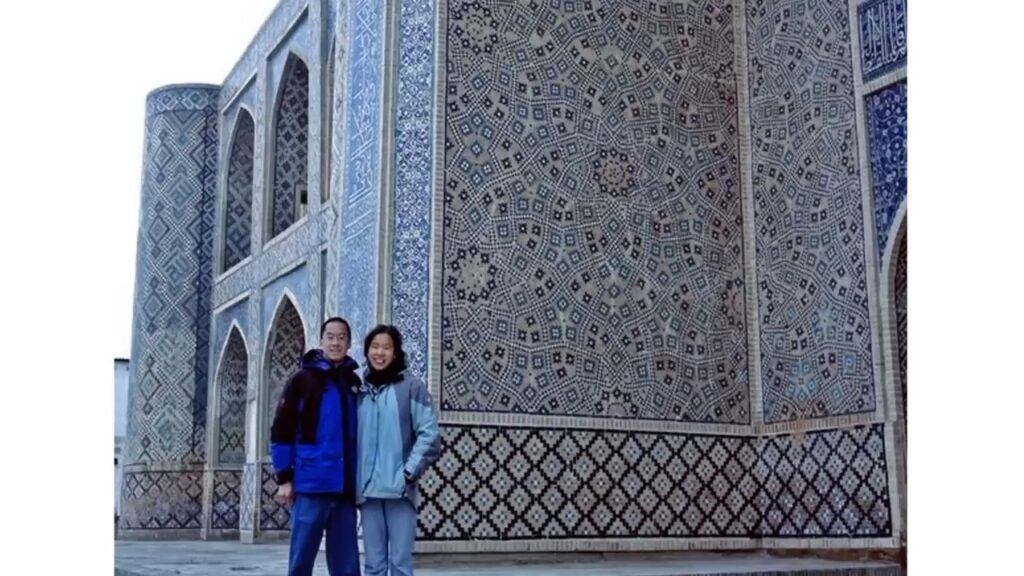

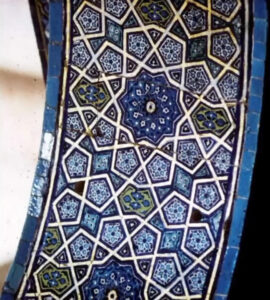

Then in 2007, the man pictured left, Peter Lu, who was then a graduate student in physics at Princeton, discovered this pattern on a 14th century Madrasa ,while on vacation with his cousin in Uzbekistan,

After some analysis, Lu concluded that this was in fact Penrose tiling, constructed 500 years before Penrose discovery!. This information took the scientific world by storm and prompted headlines everywhere, including Discover Magazine, which proclaimed this the 59th most important scientific discovery of the year 2007.

So now we’ve heard about this amazing pattern from the point of view of mathematics and physics, together with art and archaeology. This now leads us to the question, what was there about this pattern that this ancient culture found so important that they put it on their most important building?

To try and find answers to this I looked to the world of anthropology and asked the question, what was the world view of the culture that made this? And this is what I learned.

To this culture, the pattern is a representation of life itself. And as we all know, life’s complicated!

But not only is life complicated, life is also A-periodic in the sense that every event, every happening, every decision will make the future unfold differently, often in ways that are impossible to predict.

Yet in spite of the complexity and in spite of a future that’s impossible to predict, there remains an underlying unity that holds everything together and gives rise to everything.

This is that design.

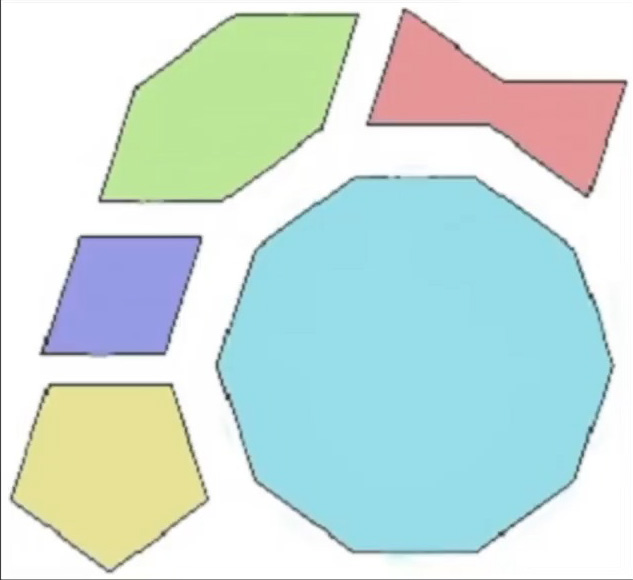

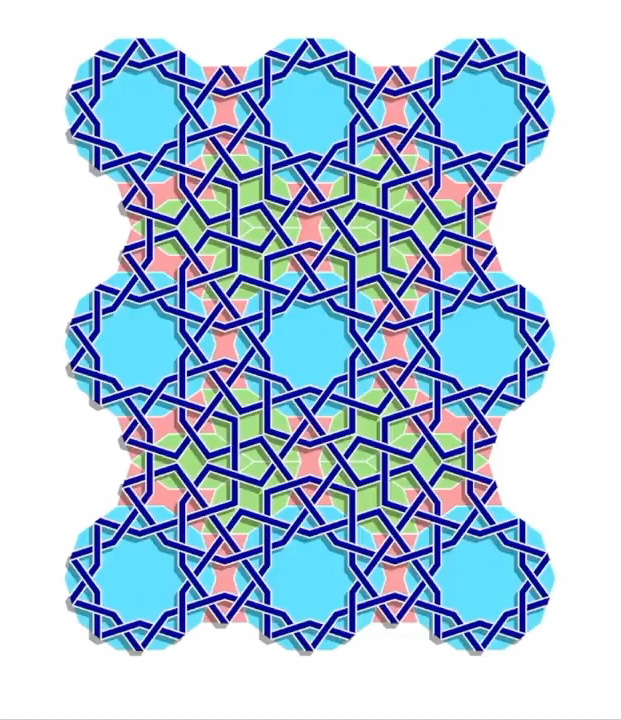

Now, it turns out this is actually based on this set of Penrose tiles, which are reducible to these shapes.

These individual tiles consist of a variety of polygons, notably a “kite” and a “dart.” Unlike regular tessellations, Penrose tiles don’t repeat exactly, thus creating patterns with an A-periodic quality. These are the individual shapes used to construct intricate and visually captivating designs, demonstrating the concept of self-similarity and challenging traditional notions of tiling and symmetry.

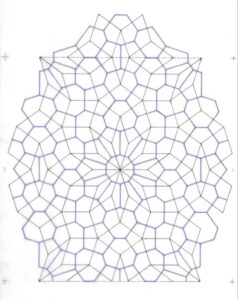

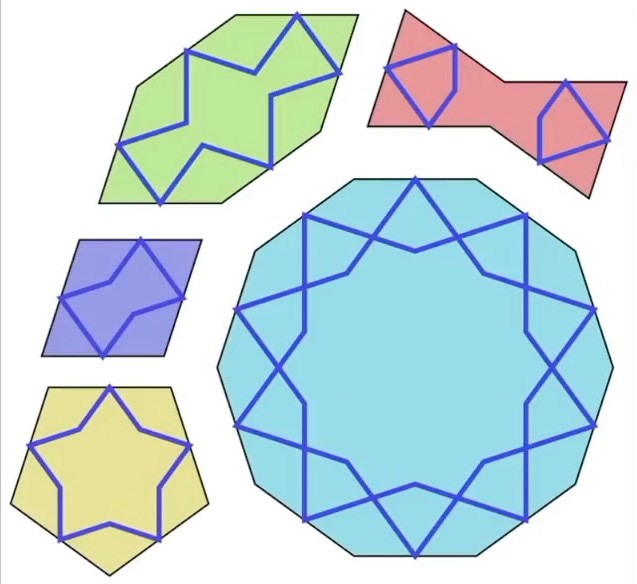

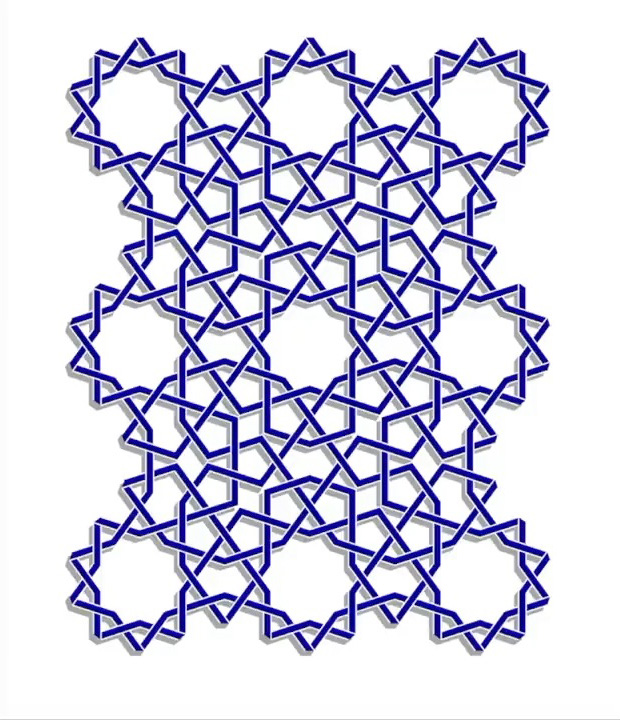

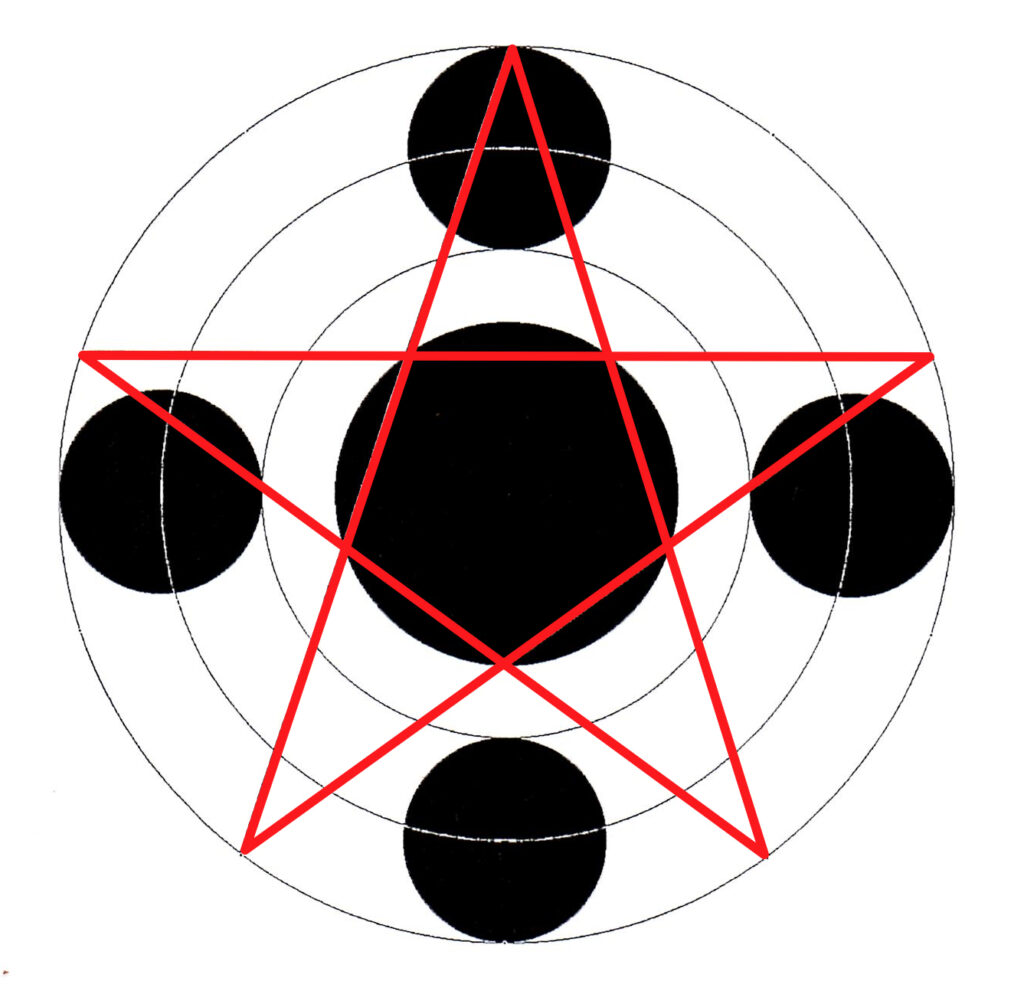

In order to draw these shapes, the medieval craftsmen who did this would have done them by using these construction lines.

It seems highly likely that these medieval craftsmen, especially those working on intricate architectural and artistic projects, used similar geometric principles to create visually appealing patterns. Medieval craftsmen often had a deep understanding of geometry, and they employed various techniques such as compass and straightedge constructions to create complex designs that showcased their artistic and technical skills.

These craftsmen clearly achieved a sense of hidden unity and A-periodic patterns through their understanding of geometry and symmetry, but it’s important to recognize that they did this hundreds if not thousands of years before Penrose discovery.

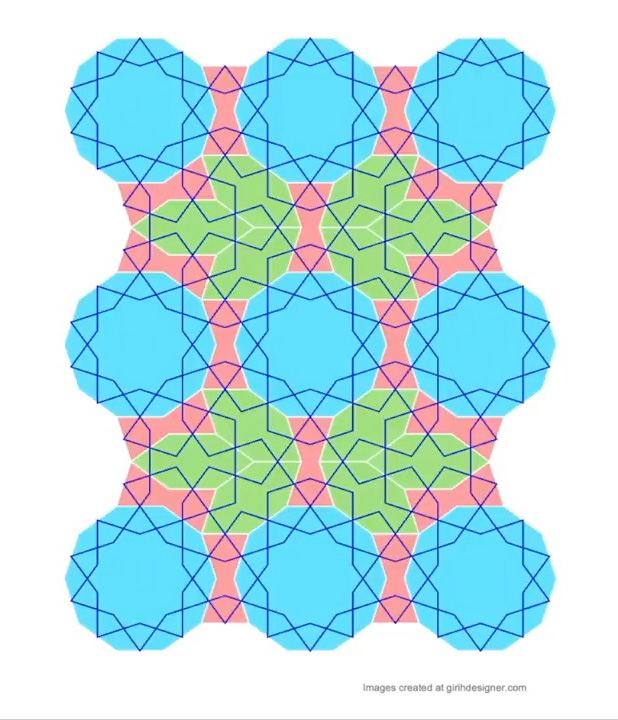

Of course, these construction lines don’t appear in the final work.

But if we add them back, it would look like the image above.

Then if we add the weaving it would look like the image below:-

Weaved construction lines, also known as “Penrose lines” or “cut-and-project” lines, are an essential part of the Penrose tiling technique. These lines are used to create the A-periodic patterns of Penrose tiles. The process involves alternating long and short construction lines that intersect at specific angles.

By carefully arranging these weaved lines and placing Penrose shapes along them, the tiles are positioned in a way that ensures they can fill a plane without overlapping or leaving gaps. The angles at which the lines intersect match the angles of the Penrose shapes, enabling the tiles to fit together seamlessly, despite lacking translational symmetry.

This approach of using weaved construction lines and non-repetitive shapes allows for the creation of captivating and visually intricate patterns that possess both mathematical elegance and artistic appeal.

If we hide the tiles and just look at the construction lines, we see this.

Image below taken from the Madrasa in Uzbekistan.

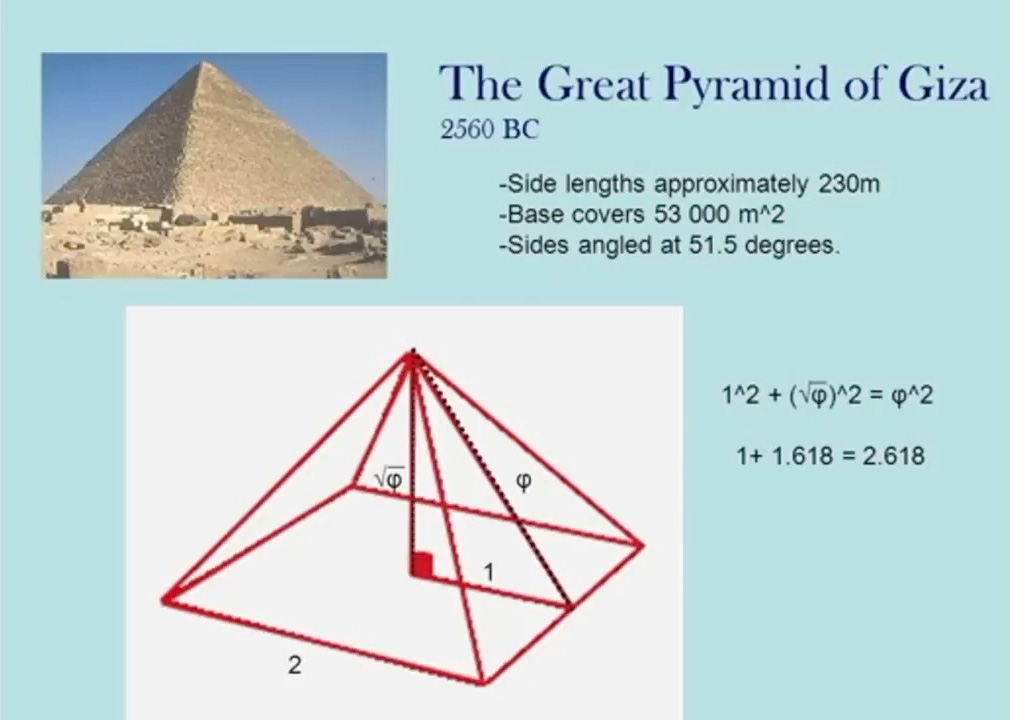

The concept of hidden unity, as seen in the patterns of Penrose tiles, has intrigued researchers who study ancient sites around the world. It’s now certain that ancient civilisations incorporated a similar idea of A-periodic patterns and hidden unity in their architectural designs and artworks.

One example often cited is the use of non-repeating motifs in Islamic architecture, where intricate geometric patterns adorn mosques and palaces. These patterns reflect a deeper philosophical understanding of unity in diversity and the inter-connectedness of all things.

Seems strange that this was only really discovered in 2007!!

Clearly, there’s an underlying structure and unity to things that seem to be complex and A-periodic.

It turns out this notion of a hidden underlying unity was common throughout the ancient world. One sees it in Egypt, Greece, Australia, Meso-America, North America, Europe, and in the Middle East.

Incorporating Penrose-like ideas, ancient builders might have aimed to create designs that appear chaotic on the surface but reveal an underlying order and harmony upon closer inspection. This concept aligns with the esoteric beliefs of some cultures, which emphasize the inter-connectedness of the universe.

Now, in the modern West, we might call this underlying unity God, but throughout the ages, other terms have been used to describe the same thing. This is what Plato called ‘first cause’ or ‘prime mover’.

In the medieval period, the philosopher Spinoza called this the ‘singular substance’.

In the 20th century, a number of terms were coined to describe this, for example, philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, who called this the “undifferentiated aesthetic continuum”. Doesn’t that have a 20th century sound to it?

Personally I like the term coined by the great 20th century physicist David Bohm, who called this the ‘Implicate Order’.

So what’s the takeaway here?

Very simply, it’s this. When we see these wonderful designs created by cultures that are separated from our own by thousands of miles or thousands of years, we can know these aren’t decorations.

These designs are statements about the fundamental values that these cultures had, what they found important, how they saw themselves, the world, and how they identified themselves in the world.

It has been said that architecture is a book written in stone. So when we see these amazing designs, we can know they’re not decorations, they’re a statement, they’re a message, just like the Crop Circles.

If you take the time to look and listen, you can hear their voices.

Crop circle image courtesy of Frank Laumen. More of his amazing work can be seen www.ancient_stones.com. http://www.ancient-stones.com/?fbclid=IwAR2D1_pLFA98fxD5EOlxUZkumJiFUrDHjS_4K3jopdgdv20jC1T0-DPMViI

Diagram: Upton Scudamore quintuplet, credit John Martineau.